Is your next outdoor adventure taking you to new heights? High altitude destinations like Machu Picchu, Sierra Nevada, Rocky Mountains, or Everest Basecamp attract hikers and adventure enthusiasts from around the world with their breathtaking views – literally!

If you’re planning a hiking or backpacking trip in a high altitude area, you should know how to identify and manage altitude sickness. Fortunately, you can take preventative measures to minimize your risk of getting altitude sickness and avoid cutting your expedition short.

This guide will walk you through the causes and symptoms of altitude sickness, treatment options, signs of advanced altitude sickness, and prevention strategies to nip altitude illness in the bud.

*This article was reviewed by Victoria Bandera. Vicky has a Master’s degree in Health and Exercise Science from Colorado State University and is an ACSM certified Exercise Physiologist.

What Is Altitude Sickness?

At higher altitudes, the air becomes thinner as oxygen levels decrease. The lower barometric pressures of high altitudes lower the partial pressure of oxygen in the lungs. Oxygen deprivation limits the ability of red blood cells to carry oxygen from the lungs to body tissue. The lack of oxygen in the blood supply is what causes acute mountain sickness (AMS), more commonly known as altitude sickness.

In a nutshell, altitude sickness happens when your body is exposed to low oxygen levels at a high elevation over an extended period of time.

You don’t pass out from oxygen deprivation while flying because aircraft cabins are pressurized to an altitude range generally between 6,000 and 8,000 feet. Mountain climbers that scale 8,000-meter peaks often depend on supplemental oxygen at extreme altitudes where oxygen availability drops by up to 67%.

Even if you don’t plan to summit Mount Everest anytime soon, altitude sickness can still affect you at lower elevations. Without proper acclimatization, hikers can feel the effects of altitude sickness even in places like the Grand Canyon, where the canyon’s rim sits 7,000 feet above sea level.

Signs and Symptoms of Altitude Sickness

We know that altitude sickness is caused by not having enough oxygen in the body. Thankfully, if you know what to look for, altitude sickness is easy to detect. Anytime you’re hiking at or above an elevation of 8,000 feet (or 2,500 meters for our metric friends), you should stay alert for altitude sickness symptoms.

Symptoms of mild, short-term altitude sickness appear 2 to 12 hours after reaching high altitude. These symptoms can include:

- Sudden headaches

- Dizziness

- Nausea and/or vomiting

- Sudden fatigue or loss of energy

- Shortness of breath

- Loss of coordination

- Decreased urination

- Loss of appetite

- Increased heart rate and/or heart palpitations

How To Treat Altitude Sickness

Descending to a lower altitude is the fastest and safest way to combat altitude sickness. Many people start feeling better even after a small change in elevation.

If you’re only feeling mild symptoms of altitude sickness or descending is not an option for whatever reason, use the following treatment options for short-term relief until you’re able to reach lower elevation:

- Stop ascending and stay put at your current elevation until your symptoms subside or you can safely descend

- Rest up and give your body time to adjust to the altitude

- Drink plenty of water and other fluids to prevent dehydration, which can worsen the symptoms of altitude sickness

- Eat small, frequent meals and snacks rich in carbohydrates and salt, like ramen, freeze-dried backpacking meals, chips, and salted nuts/seeds

- Take over-the-counter medications like ibuprofen or aspirin to relieve headaches

Who Can Get Altitude Sickness?

While anyone can get altitude sickness, three primary factors determine a person’s susceptibility and risk level: elevation at the destination, rate of ascent, and exertion.

Essentially, the higher you go, the more likely you are to get altitude sickness. Moving from sea level to high altitude too fast, whether on foot or in a car, can also increase your chances of getting altitude sickness.

Hiking takes a lot more effort at higher elevations, and overexertion is a common problem. While hiking, your lungs are working overtime to make sure your body has enough oxygen and energy to function. While proper training can limit overexertion to an extent, even the strongest hikers can fall victim to altitude sickness.

Kids are just as susceptible to altitude sickness as adults; with those over 50 being slightly more at risk. People with pre-existing medical conditions like heart failure, angina, sickle cell disease, pulmonary conditions like hypoxemia, or obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) should consult their physician before traveling to high altitudes.

The way someone has handled high elevations in the past can offer a reliable indication for future trips if the elevation and rate of ascent are similar, but it’s not always accurate. Even if you haven’t experienced symptoms at high altitudes before, it doesn’t mean you won’t in the future.

If you’re still unsure about your risk of getting altitude sickness on your next mountain adventure, use the guide below to help you assess your risk level.

Low Risk:

- You have no history of altitude sickness.

- You’re ascending to less than 9,000 ft (2,750 m).

- You’re taking 2+ days to arrive at 8,200–9,800 ft (2,500–3,000 m), with gradual increases in sleeping elevation of less than 1,600 ft (500 m) per day, and an extra day for acclimatization for every 3,300 ft (1,000 m) of elevation gain.

Moderate Risk:

- You have a history of altitude sickness and ascending to 8,200–9,200 ft (2,500–2,800 m) or higher in 1 day.

- You have no history of altitude sickness and ascending to more than 9,200 ft (2,800 m) in 1 day.

- You’re ascending more than 1,600 ft (500 m) per day above 9,900 ft (3,000 m), but with an extra day for acclimatization for every 3,300 ft (1,000 m) of elevation gain.

High Risk:

- You have a history of altitude sickness and ascending to more than 9,200 ft (2,800 m) in 1 day.

- You have a prior history of HAPE or HACE.

- You’re ascending to more than 11,400 ft (3,500 m) in 1 day.

- You’re ascending more than 1,600 ft (500 m) per day above 9,800 ft (3,000 m), without extra days for acclimatization.

- Very rapid ascents (ex: climbing Mt. Whitney or a Colorado 14’er in a day).

Can Altitude Sickness Be Lethal?

While altitude sickness itself does not cause death, ignoring symptoms and continuing to ascend can lead to more advanced cases of AMS that, if left untreated, may be fatal. Without early intervention, altitude sickness can lead to high altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE) or high altitude cerebral edema (HACE).

What Is HAPE?

HAPE, or high altitude pulmonary edema is a condition characterized by fluid accumulation in the lungs, which makes it difficult to breathe. The low atmospheric pressure at high altitudes causes the body’s fluids to become imbalanced. As a result, fluid begins to leak into the air spaces of the lungs, limiting airflow and oxygen supply to the body.

If left untreated, HAPE can be life-threatening. The symptoms of HAPE differ from mild to moderate altitude sickness. As soon as you notice any of the following symptoms, seek immediate medical attention. The symptoms of HAPE include:

- Cyanosis (i.e., skin, nails or whites of the eyes start to turn blue)

- Confusion and irrational behavior

- Shortness of breath even when resting

- Tightness in the chest

- Extreme fatigue and weakness

- Feeling like you’re suffocating at night

- Persistent cough, bringing up white, watery fluid

What Is HACE?

HACE, or high altitude cerebral edema, is a severe condition that occurs when fluid accumulates in the brain, causing swelling and pressure. HACE is a rare form of altitude illness, but should be diagnosed and managed as soon as possible, as it can lead to coma and death within 24 hours after symptoms begin. Symptoms of HACE include:

- Headache

- Loss of coordination

- Severe exhaustion or weakness

- Disorientation, memory loss, hallucinations

- Psychotic behavior

- Coma

HAPE and HACE pose life-threatening risks to hikers. These more severe types of altitude sickness require immediate medical attention.

Side note: In situations like these, a PLB (like an InReach or SPOT device) can mean the difference between life and death. Altitude sickness notwithstanding, a PLB is an invaluable safety and navigation tool that can provide life-saving assistance in a backcountry emergency.

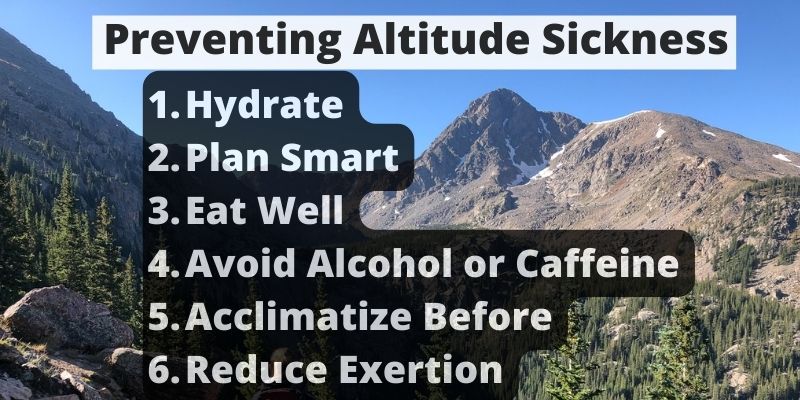

How To Prevent Altitude Sickness

Climbing at a slow, measured pace is the best way to prevent altitude sickness. While minor altitude sickness may be a foregone conclusion for many hikers, you can prevent it from escalating into a more severe condition with proper risk assessment and sharp decision-making skills.

These three principles will help you ward off, or at least minimize, the effects of severe altitude illness:

- Learn how to recognize the early symptoms of altitude sickness.

- Avoid sleeping at a higher elevation if you have altitude sickness.

- Descend if your symptoms don’t get better or get worse while you rest.

On top of that, there are additional preventative measures you can take to prepare your body for hiking at elevation.

- Stay hydrated: Dehydration is a common challenge hikers encounter at higher altitudes. Dehydration disrupts the mineral balance in your body and affects its ability to function properly. Humidity is low at high altitudes, which causes water to evaporate from the body faster. It’s easy to think if you’re not sweating you’re not dehydrated, but that couldn’t be further from the truth. If you’re not losing water through your pores, you’re losing it through urination. Increased urine production, or high altitude diuresis, occurs when your kidneys react to the dry climate of high elevation by releasing hormones to regulate blood thickness in the absence of adequate oxygen.

Hiking at high elevations also increases your respiration rate. As your body works double time to get as much oxygen as possible, all that huffing and puffing causes you to lose more water, leading to further dehydration. So how much water should you drink at altitude?

Even before you reach your destination, you should start hydrating. Drink plenty of water in the days and hours before traveling to a high altitude area. Once you start hiking, maintain a consistent hydration routine to minimize your odds of getting altitude sickness. Drink an extra 1-1.5 liters of water daily at high altitude, for a minimum of 3-4 liters depending on your mileage, total elevation gain, temperature, and exertion.

- Plan smart: A common misconception about trekking at high altitude is that physical condition dictates the body’s ability to fend off altitude sickness. Many people “in peak shape” skip acclimatization, go too high too fast, and get into trouble because of this.

As you plan your upcoming adventure in the high country, pencil acclimatization days into your itinerary. It takes time for your body to adapt to high altitudes. Try to acclimatize at 8,000-9,000 ft (2,500–2,750 m) for 3-5 days before you hit the trails, allowing everyone in your group time to adjust before ascending. If you and your group have rested for 24 hours without incident, you’re safe to climb higher. Treks at altitude should avoid big single-day elevation gains (more than 2,000 vertical feet).

If your itinerary involves a lot of elevation gain, plan your camp locations at lower elevation. Sleeping at high elevation keeps your blood oxygen level low. Adjust your trip plan so you’re climbing over mountain passes during the day and returning to lower altitude at night to reduce stress on your body (i.e., climb high, sleep low).

- Eat well: Your body is doing more work than usual so make sure to stay nourished. Carbohydrates are your body’s preferred energy source, especially at high altitudes. At least 60% of your daily calories should come from carbohydrates. Good sources of carbohydrates you can throw into your pack for your high altitude trek include energy bars, dried fruit, nuts and seeds, tortillas, bagels, and instant oatmeal.

- Skip the coffee: Avoid alcohol or too much caffeine, as they can dehydrate you more quickly at high altitudes. Booze and caffeine worsen the effects of dehydration due to their diuretic properties that occur in high-elevation areas. Instead, drink plenty of water, swap your daily cuppa for some herbal tea, and save that beer for summit day.

Medications and Remedies to Help Prevent and Treat Altitude Sickness

If you’ve chugged water and hiked at a snail’s pace all day, but you’re still feeling the telltale signs of altitude sickness, there are a few over-the-counter medicines and nutritional supplements you can take to alleviate your symptoms.

- Bring a few over-the-counter pain medications like Advil, Tylenol, or aspirin for headache relief.

- Take promethazine or Tums to calm nausea or an upset stomach.

- Add electrolytes like Liquid IV, Gatorade, Scratch, or Nuun tablets to your water to prevent dehydration and keep your sodium and potassium levels in check.

- If you know your body doesn’t play nice with altitude, see if your doctor can write you a prescription for Diamox, a medication that prevents severe altitude sickness. Diamox works best when taken several days prior to being at altitude.

Final Thoughts

No amount of muscle power and determination can help you overcome altitude sickness, but there are steps you can take to minimize and manage the symptoms when you’re out in the backcountry. Whether you’re climbing a Colorado 14er or hiking to Everest Basecamp, you’ll have everything you need to thrive in high altitude environments and adventure above the clouds with confidence!

Ash Czarnota is a freelance writer based in Southern California with over 3,000 trail miles under her feet. She is the founder of Go Galavanting, an online community to celebrate adventurous women and highlight emerging thought leaders in the outdoor industry. A PCT alumni, Joshua Tree enthusiast and burgeoning climber, Ash uses her outdoor experiences to craft content that educates and inspires a rising generation of adventurers to embrace their inner wild. Connect with her on Instagram (@salty_millennial).

-

Beauty

-

Parking

-

Trail Conditions