If you’ve ever been hiking in the mountains, or just on hilly terrain, it’s likely that you’ve encountered a switchback. A switchback is a deceptively simple trail engineering principle that has its roots in ancient roads and paths. The mechanism behind switchbacks can be seen in trails that are thousands of years old, and can be found all over the world, from Machu Picchu to your favorite state park.

Quick Navigation:

What Is A Switchback? | History Of Switchbacks | Switchbacks Vs Climbing Turns | Switchback Safety & Etiquette

What Is a Switchback?

A switchback is a type of trail or path that takes a zig-zag pattern up steep terrain, such as a hillside or mountain. They can frequently be found in mountain passes, as they are one of the safest ways to traverse steep terrain.

Switchbacks work by exchanging a single path of a steep grade for several paths of a lesser grade. Rather than climbing directly up a slope, switchbacks wind from one side of the slope’s face to the other, then back again. This creates a longer path— but may not actually take much more work to climb, since the switchback path has a gentler slope and doesn’t require the energy of a steep climb.

History: Developing The Switchback & Famous Examples

While ancient trailblazers and road-builders didn’t always record their path-planning decisions, there are numerous examples around the world of ancient cultures understanding that switchback trails are safer, more efficient, and easier to traverse than paths just straight up a hill or mountain. Some of these trails from antiquity are even used today by visitors to these ancient places.

Along the Andean coast of South America, the Inca road system used switchbacks lined with stone to move caravans of llamas between cities. The Inca built their roads across deserts, rivers, gorges, and mountain passes, and many of their original switchbacks can be seen and traversed at sites like Machu Picchu.

In the Middle East, the automobile route that is now known as the King’s Highway was originally a serpentine mountain path for foot travel. Renovated and widened by the Roman emperor Trajan, this is one of the oldest continually used routes in the world and features numerous switchbacks as it snakes through the desert and mountains towards the coast.

Roads in the Khyber Pass, which connects the Indian subcontinent to the rest of Asia, were first developed in the 5th century after Darius the Great of Persia conquered the lands around what is now Kabul and expanded his empire to the Indus River. As part of the ancient Silk Road trading route, switchbacks in the Khyber Pass were only used during the late spring and summer seasons, as even with switchbacks the paths were too treacherous to use during the rest of the year. Switchbacks are common features of Nepali and Himalayan roads and trails as well, and are often the only way to get up some of the mountains there.

In South Africa, the Sani Pass is another famous old switchback trail. First developed as a bridle path in 1913, this path was foot-traffic only until 1948. This path is traversable with 4×4 vehicles, but many who use it take it by foot or by pack animal. Today, the Sani Pass connects South Africa and Lesotho.

While ancient roadbuilders used switchbacks, there is no evidence as to who used them first. The idea might not even originally have been human! When left to their own devices, sheep have been observed unintentionally creating paths with switchbacks, as you can see here. Alpine goat paths in Europe follow similar patterns, so it could be that these herd animals (which were first domesticated in mountainous regions) have a natural instinct to take safer switchback routes.

While the switchback’s ancient history might be murky, by the 19th century, American mining companies had perfected and mechanized the switchback. The gentle slopes led to the creation of the gravity railway, which made it possible to transport people and goods downhill using only the power of gravity, saving labor and fuel costs. People also found the hairpin turns fun, which in turn led to the creation of the Gravity Railway, the first roller coaster at Coney Island!

Switchbacks Vs Climbing Turns

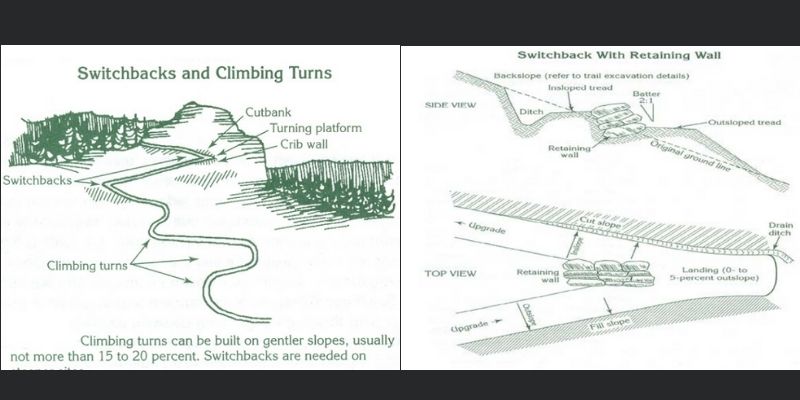

Switchbacks and climbing turns are both used to reverse the direction of travel on hillsides steeper than a 15 percent grade.

How Are Switchbacks Different From Climbing Turns?

In general, switchbacks are sharper turns, used on steeper slopes, and at each corner, known as the landing, the grade is less steep, between 0-5%. Climbing turns do not have landing areas (sharp corners) and have a turn radius of 15-20 feet, which is much larger than a switchback.

Switchbacks construction is generally more complex as drainage, and landings require more thought and effort. This makes switchbacks more expensive to build than climbing turns. Switchbacks therefore are often only used in applications where they are absolutely needed. This occurs when slopes are too steep for climbing turns, which is generally when a slope exceeds a 20% grade. At this grade, it is extremely difficult or impossible to maintain a trail without well constructed switchbacks and landing areas that drain properly and avoid erosion. When climbing turns are created on slopes that are too steep, they often erode, and may need to be replaced with switchbacks.

Switchback Safety

In addition to making things easier and more convenient for a hiker, switchbacks are an important safety feature of mountainous trails. If you’re hiking somewhere that’s extremely steep with uneven terrain, the gradual gradation of a switchback can keep you from seriously injuring yourself.

Switchbacks also provide an easier way to deal with elevation than a path straight up a mountain. Changes in elevation occur over shorter sections, helping you pace your upward journey and adapt better to the elevation and pressure. Switchbacks also allow hikers to avoid hilly hazards like loose rocks, drop-offs, waterways, or dense brush.

When you’re hiking, it’s important that you don’t just pay attention to whether or not a switchback is present, but also where the landing is and what the backslope of the trail itself is. Though the definition of a switchback might be simple enough, the actual engineering of such a trail may require adequate excavation and structuring the fill dirt to hold a trail. Switchbacks aren’t just a trail meandering up the side of a mountain— they’re cut into the mountain itself, often scooped away from it, which can make them much more stable than other kinds of trail.

Switchback Etiquette

It’s important that you stick to pre-established switchbacks whenever you can. Creating a shortcut by hiking straight up and skipping the zigs and zags of a switchback is detrimental to the soil and local vegetation. By creating a straight path, you aren’t just breaking trail etiquette, you’re creating more avenues for erosion.

As water flows down a vertical path, it takes soil with it, creating or deepening ruts and even causing small mudslides. Switchbacks, however, are more or less horizontal. This causes the water to puddle and seep into the ground, because there is a less clear path of least resistance for gravity to pull it along. Furthermore, as switchbacks are intentionally constructed, many of them were built with drainage in mind. The switchback might have rocky drainage, water bars, or other fast-draining water removal that can deal with running or standing water. The same cannot be said of the uncut trail area between the lengths of the switchback.

Additionally, the areas between the paths of a switchback are habitat for plants and wildlife. The ground cover here also protects the ground from erosion, and many switchback trails are groomed with netting between the different levels. This helps protect the trail and the hillside from erosion, and makes it even more difficult to take or create a shortcut between the levels of the path.

Depending on where you are, you should also be careful when passing other groups on a switchback. Switchbacks can be quite narrow, so make sure that you communicate with your buddies and any other hikers you might see on the trail. Generally speaking, the corners are often wide enough to let other hikers pass by. Like most hiking scenarios, hikers heading down should give hikers heading up the right of way.

Navigating Switchbacks

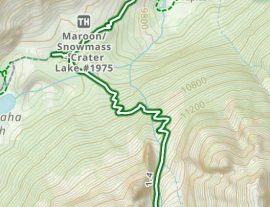

When you’re reading a topographic map, switchback trails can look very misleading. Since they are by default a relatively straight trail, it can be confusing to look at the curves of a topographic map and see a hard line zigzagging across. Switchbacks are built to decrease grades from high angles to an angle of 15-20º, and on your map, they’ll look like big Zs across the topography. These Z-shapes are often less dramatic from a 3 dimensional perspective, but they’ll stand out on a detailed topographic map.

Because switchbacks are so carefully engineered and constructed, you won’t need any kind of special trail gear. They are designed to minimize erosion and standing water, so even your feet shouldn’t get too wet! However, if you are a hiker or backpacker who uses poles, these can help you navigate the ends of a switchback and help you make tight turns. This is especially useful for trail runners or people who need to take the corners quickly. Poles can also help you find where exactly the switchback goes next at its turns and can keep you out of the undergrowth. In winter, they can help make the need for traction less necessary, or minimally, more effective.

While hiking a switchback trail, you should still stick to general hiking safety protocols. Switchbacks make a trail safer, but there’s always some risk when you go out hiking. Just because a hike may have switchbacks at the steepest sections, doesn’t mean a change in necessary gear or preparedness.

Tips For Hiking Switchbacks

As someone who his taken far too many switchbacks than I could count, absolutely suffered on many, and conquered many more, here are some tips to make them more manageable.

Consider Hiking Poles

Hiking poles can help reduce fatigue on the legs by leveraging more of your upper body. Read our in depth article on hiking with and without poles for more information.

Train For Elevation Gain

The best way to train for switchbacks is to simply hike more! If that isn’t possible, doing lots of stairs, or the stairclimber at the gym can also be great options. Most treadmills have the ability to incline pretty substantially, and it is a great idea to max out your treadmill to get your body and muscles used to powering up steep hills.

Pay Attention On Trail

Switchbacks can make it difficult to see what’s coming down the trail towards you. This is especially important on trails where there may be mountain bikers, trail runners, or even horses. Pay attention to ensure you don’t have any collisions.

Adjust Your Stepping Cadence and Length

Switchbacks, and hiking in generally can be very repetitive. Which can be great for crushing miles and vertical gain, but it also can be brutal. When we are hiking steep inclines, whether switchbacks or not, we will often occasionally switch our cadence and step lengths. For example, switching to a shorter stride and faster turnover with each step, and then going back to normal. This can help switch things up which can be nice on the muscles, but also on the mental state.

Conclusion

Switchbacks are a trail feature you might take for granted, especially if you spend a lot of time hiking in the mountains. But knowing what they are, what they look like, and how important they might be to a trail’s ecosystem makes it easier to appreciate switchbacks for what they are. The next time you or a hiking buddy is tempted to think about shortcutting a switchback, we hope you remember and think for just a second about all the advantages of keeping yourself on the switchback!

Max DesMarais is the founder of hikingandfishing.com. He has a passion for the outdoors and making outdoor education and adventure more accessible. Max is a published author for various outdoor adventure, travel, and marketing websites. He is an experienced hiker, backpacker, fly fisherman, backcountry skier, trail runner, and spends his free time in the outdoors. These adventures allow him to test gear, learn new skills, and experience new places so that he can educate others. Max grew up hiking all around New Hampshire and New England. He became obsessed with the New Hampshire mountains, and the NH 48, where he guided hikes and trail runs in the White Mountains. Since moving out west, Max has continued climbed all of the Colorado 14ers, is always testing gear, learning skills, gaining experience, and building his endurance for outdoor sports. You can read more about his experience here: hikingandfishing/about